Fire is a key part of our storyscape in California.

Depending on whom you talk to, stories about fire range the gamut from nostalgia to terror. For most people, fire is a thing either confined to a fireplace (or campfire pit) or a devastating force producing smoky orange skies and moonscapes. And for most government agencies, until recently, fire was a thing to be fought, controlled, and suppressed.

Climate change has brought a new reckoning with fire. Most of what we thought we knew: about how wildfires behaved, how to protect our homes and communities, and how to flee fire and deal with the aftermath, has quite literally gone up in smoke. Today’s massive wildfires create their own weather, destroy ancient trees in temperate and montane rainforests that we thought were impervious to fire, often move too quickly for people to safely evacuate, and demolish even the most well-built (to strict building codes) and well-landscaped homes.

In California, over one million people have been evacuated fleeing wildfires, and I was among them – twice. As soon as the surrounding landscape begins to dry down, I get nervous, because I know that fire season is now year-round in California. I have four different fire alert apps on my phone, and they have come in handy: one summer when I was in Portland (OR), I was alerted to a fire in the vicinity of an Wailaki/Pomo/Wintu/Tolowa uncle [who didn’t do email, or internet, or smartphones] who lived in a remote portion of a Tribal reservation. I reached him in time for him to evacuate to the coast, where he remained until it was safe to return.

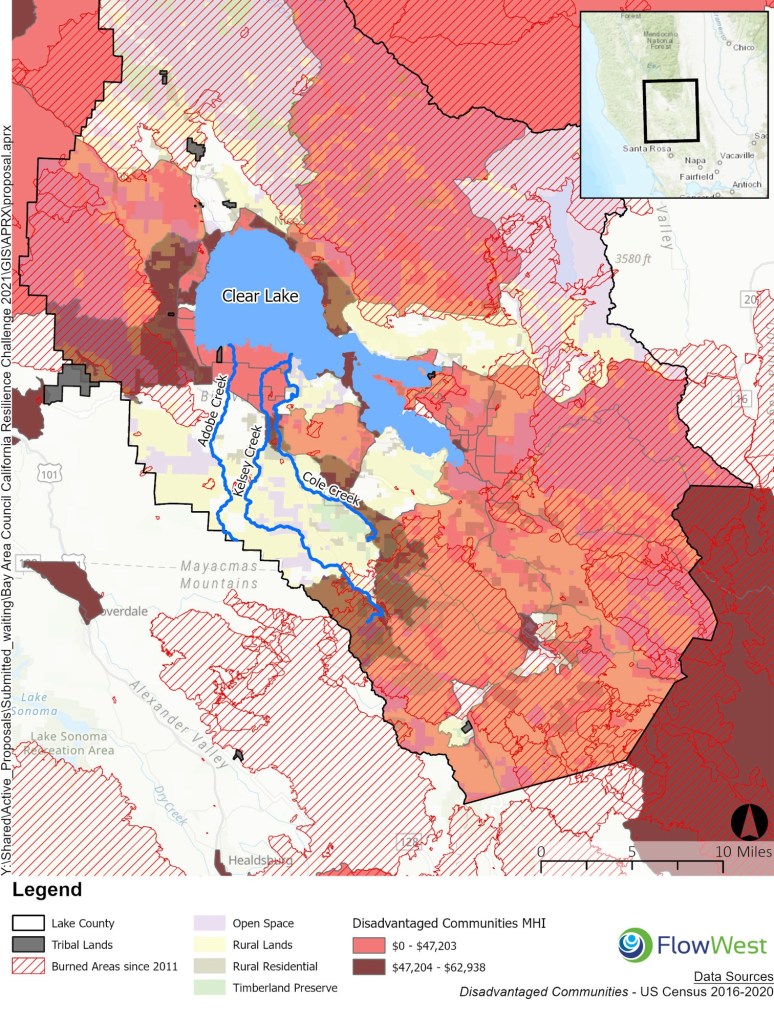

Lake County – my new home – has been repeatedly burned by massive wildfires, including a fire (the Ranch Fire, or Mendocino Complex Fire) that at the time was the largest in California. Everyone I work with here has dealt with multiple fires: they have assisted with neighborhood evacuations and disaster relief efforts, created wildfire resiliency plans, monitored ancestral cultural sites revealed by fire, and/or their homes have been partially or completely destroyed by fire. One group of colleagues – whom I’ll be talking more about in a bit – are transforming our collective relationship with fire by bringing “good fire” (also known as culturally burning) back to Lake County.

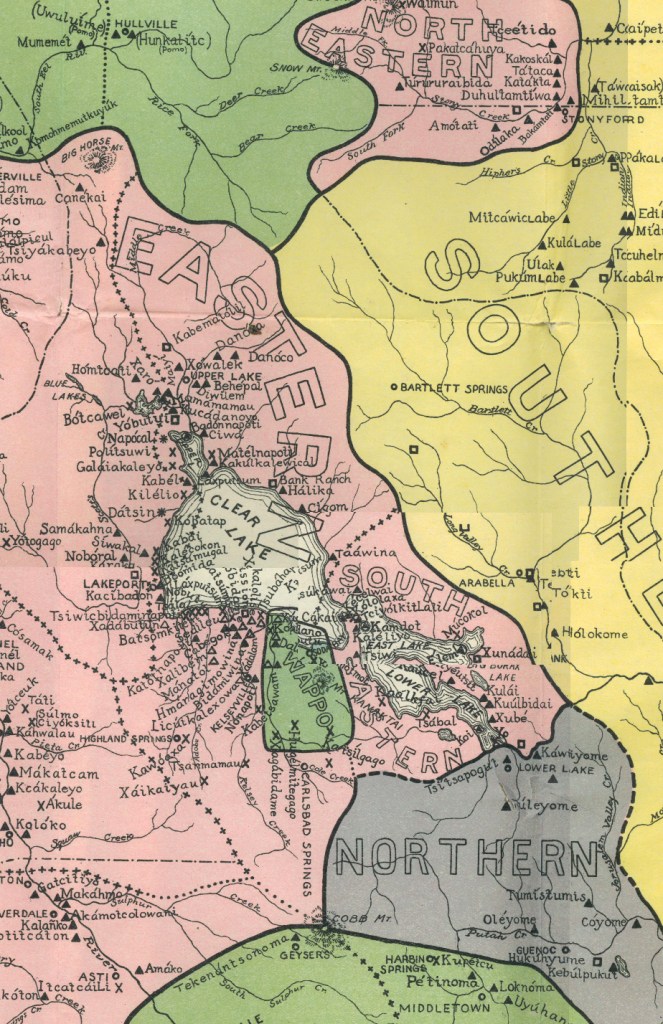

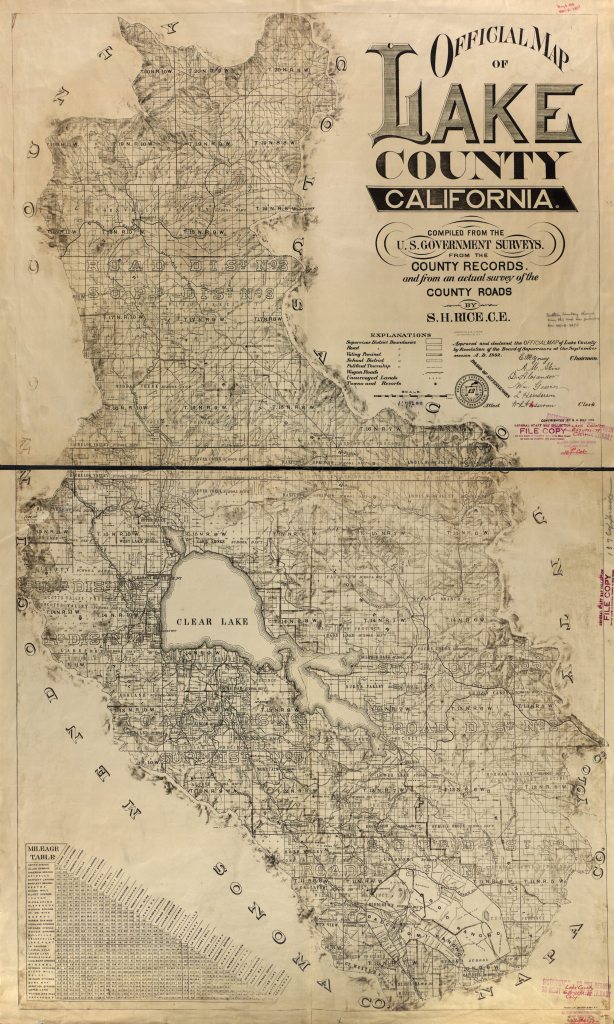

Lake County is a storyscape where two distinct realities coexist. In one reality, the entire county was once the homelands of First Peoples who resided here for thousands of years and stewarded the lands with fire (amongst other ecologically sophisticated techniques), and the storyscape has suffered as a result of the peoples being separate from their lands. In the other reality, the county is fragmented into thousands of pieces owned by countless entities – some who can claim multi-generational residency, but mostly not – and its storyscape has prospered because the land was turned into tourist attractions, agricultural and mineral production.

There is not much nomenclature overlap between these two maps: different realities = different sets of names.

These disparity between the realities of the First Peoples versus the Unsettlers are demonstrated in maps that were created around the same time: one by an ethnographer (Samuel Barrett – see an excerpt from his map prepared during 1903-1906 to the left), another by the U.S. Government (see the 1892 map to the right, obtained from the Library of Congress).

Accompanying these separate realities, there are some hard facts about Lake County that we all share:

(1) Over 60% of the landmass has been burnt by catastrophic wildfires in the past decade, in large part due to ecologically ignorant land use practices (enabling invasive grasses, conifer encroachment, overly dense woodlands and ground fuels build-up) and the loss of indigenous stewardship (consistent vegetation trimming, prescribed burns, and watershed conservation);

(2) The median income level ($32K) for county households (averaging 2.5 people) is less than the federal poverty level for a household of two people plus one kid ($34K);

(3) Lake County is one of the least [scientifically] literate counties in California. Only one-tenth of our residents have a bachelor’s degree (or higher; versus an average of 20% statewide), and less than half of our high-schoolers graduate (versus 84% of high-schoolers throughout California).

(4) Lake County’s Clear Lake is both the most ancient and one of the most polluted lakes in North America, due to an EPA Superfund site on the southeastern end (smack on top of, and adjacent to, the Elem Indian Colony Tribal reservation), a host of invasive species that result in ecological imbalances, ongoing harmful/toxic cyanobacteria/algal blooms during the warmer months, and legacy DDT pollution from several generations back (when County officials attempted to rid the lake of an endemic, non-biting gnat for the benefit of tourists).

I cite these daunting statistics because they have everything to do with Lake County’s storyscape and current efforts to co-create a healthier and more equitably shared storyline for county residents going forward.

(PHOTO CREDIT: Jeanine Pfeiffer)

Like many other regions in California, Lake County has tremendous ecological diversity: from endemic fish species inhabiting shallow freshwater to alpine plants on rocky mountaintops. Lake County also contains significant cultural diversity, in the form of seven federally recognized Tribes of Eastern and Southeastern Pomo, Lake Miwok, and Mishewal Wappo ancestry (plus other Tribal ancestry due to extensive intermarriage). For Tribes in Lake County, the bends in the streams, the rocky outcrops, the patches of willow, the elk herds, historically had names, meanings, stories, and specific uses. This knowledge, transferred inter-generationally by Culture Bearers, has largely disappeared, or is fragmented: the current generation of cultural learners (younger Tribal members) is in dire need of proactive measures to conserve and share the knowledge that remains.

Residing in this marginalized, poverty-stricken region located several hours NNE of San Francisco, I have been gifted with multiple consultancies, all of which involve Being the Change We Wish to See in the World alongside Changemakers and Culture Bearers. The presence of a significant group of Changemakers and Culture Bearers here is a big deal in a county that hosts the nation’s most ancient and most mercury-polluted lake, centered amidst a landmass blackened by massive wildfires, within the ancestral territories of seven federally recognized Tribes.

One of the finest group of Changemakers – whose work overlaps with mine in many arenas – are affiliated with the Tribal EcoRestoration Alliance (TERA http://www.tribalecorestoration.org). This small inter-Tribal nonprofit, peopled by young adult staffers largely from Lake County Pomo Tribes, and founded and headed by the pathbreaking activist/teacher/mother/dragon-slayer Lindsay Dailey, is bringing back “good fire” and other Tribal stewarding practices to our long-neglected storyscape.

By “long-neglected storyscape,” I mean the ecological landscape + the cultural landscape + the stories we’ve been telling ourselves about what landscapes are, were, and should, or could be.

TERA bridges the gap between Culture Bearers and cultural learners, between Tribal communities and allies, between ecosystem restoration and cultural revitalization, and between envisioning a better world and actually working to create it. TERA’s Board, staff, and crew are cross-cultural and inter-tribal, as are the communities they work with. TERA provides employment and training opportunities for countless young adults and volunteer community members. TERA crew have hand-pulled thousands of invasive plants from lake shorelines, stabilized stream banks with woven willow walls, administered good fire to oak woodlands and tule reed marshes, offered workshops in traditional basketweaving, foods, and medicines, and helped make countless properties more fire-resilient.

TERA works with an impressive array of local, state, and national entities – CalFire, US Forest Service, California State Parks, East Bay Regional Park Service, Lake County Fire Districts, Lake County Prescribed Burn Association, Robinson Rancheria, Scotts Valley Band of Pomo, Big Valley Rancheria, Habemetolel Pomo of Upper Lake, Elem Indian Colony, Round Valley Indian Tribes, Fire Forward, Fire and Music, among many others.

This year TERA is one of a handful of community-based organizations to be featured in the international publication Langscape, published by the Canadian nonprofit Terralingua. Terralingua is devoted to all things related to biocultural diversity: how biological, cultural, and linguistic diversity are intrinsically and synergistically connected, and how people all over the world document, celebrate, conserve, study, and revitalize biocultural diversity. (Biocultural diversity is a specialization I have devoted my life to, so I’m thrilled to be the contributor of this multi-media piece.)

We’re especially excited about TERA’s appearance in Volume 12, because it is the first time Langscape simultaneously published a multi-media piece online with photos, audio files (short interviews with TERA members), and a video (see this link) as well as publishing photos and interview excerpts in a gorgeous print magazine (Langscape Volume 12).

You can see the video here:

And you can download the PDF to print out, or share with others, by clicking on the link below.

Great article and important work. Thanks!

We look forward to welcoming you here to help video document our efforts!

Such good work you are doing. Thank you.

Yes, we are fortunate to have so many dedicated people of good and strong hearts 💞here in Lake County.

Thanks for sharing- very informational and exciting to read about community efforts to educate and restore balance of nature. Must be very satisfying to be a part of this and to be spreading the word. cc