“Keep the past in the past,” say deniers.

(Trigger warning: this is an essay that deals with horrific subject matter.)

In the divided United States that I live in, one of the divisions I witness daily involves people who are willing to consider uncomfortable truths vs. people who are not.

The folks who can handle the discomfort tend to grow up.

The folks who can’t handle it remain stunted.

“To be ignorant of what occurred before you were born is to remain always a child. For what is the worth of human life, unless it is woven into the life of our ancestors by the records of history?”

– Cicero

I have seen this play out in my life on a personal level (whenever I confront mistakes I’ve made or character flaws I possess), on a professional level (when I was forced to recognize and address hostile work environments) and, recently, on a societal level in my own backyard.

I live in a Northern California county with a violent history.

This is not uncommon in California, a state built upon parallel ecological and cultural genocides including (but not limited to): the Gold Rush, the State-sanctioned genocide of First Peoples (cash bounties were paid out for “Indian scalps”), the plundering of temperate rainforests (95% of the redwoods were milled) and natural wetlands (>90% lost), the widespread destruction of salmon habitat, and the wholesale robbery of water in Owens Valley (the ancestral homelands of the Bishop and Lone Pine Paiute) by the Los Angeles Water District.

This violent history, partially documented in my essay “The Language of Silence,” includes the murders, in Lake County, of the great-great-great aunts and uncles of my husband, a Tribal Elder for one of the seven remaining federally-recognized Tribes in the county.

The killings, a series of events related to The Bloody Island Massacre, occurred long enough ago that people ignorant of historical events find no current relevancy.

“The past is the past and it needs to stay there,” repeats one such ignorant person, who happens to be running for District Supervisor.

This person also claims to be a Christian, whose beliefs are based on several-thousand-year-old stories, from the past.

California’s violent history is rarely discussed by non-Natives. Amongst Natives, the remembrance of the violence – the physical, cultural, ecological, psychological, economic, institutional – violence is tightly interwoven with daily life. It is why the elders in your family had a hard time getting work, and become accustomed to deprivation. It is why you never learned your Native language or songs or traditions, because your grandparents were sent away to boarding school.

The subject of intergenerational trauma is eloquently contained in the works of Louise Erdrich, Leslie Marmon Silko, Joy Harjo, Robin Wall Kimmerer and Sherman Alexie, to name some of my favorite authors.

In this post, I will only speak to one point in history, summarized on Wikipedia:

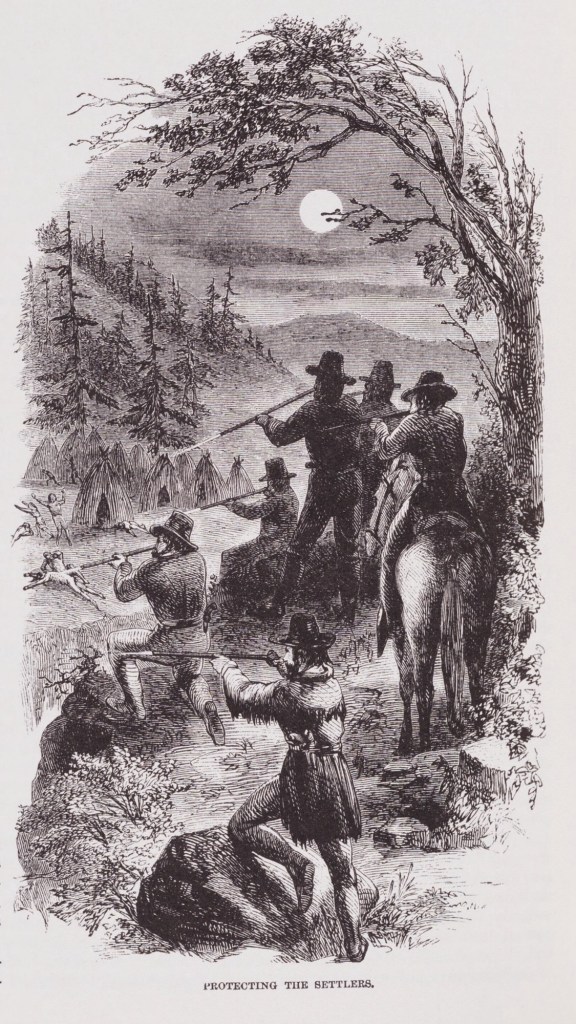

A number of the Pomo, an indigenous people of California, had been enslaved by two settlers, Andrew Kelsey and Charles Stone, and confined to one village, where they were starved and abused until they rebelled and murdered their captors. In response, the U.S. Cavalry murdered at least 60 of the local Pomo. In July 1850, Major Edwin Allen Sherman contended that, “There were not less than four hundred warriors killed and drowned at Clear Lake and as many more of squaws and children who plunged into the lake and drowned, through fear, committing suicide. So in all, about eight hundred Native Americans found a watery grave in Clear Lake.

I don’t know how else to make the story real to others, so, here goes.

Imagine if everyone in your extended family was raped, or shot, or tortured, or starved, or beaten, by a pair of degenerates.

Imagine that this truth was handed down, from generation to generation, from your great-great-grandparents.

And in this scenario, everyone knows who exactly those degenerates were: there’s no question about their actions, their guilt, or their names.

This historical reality is one that you, and everyone you know, has embedded into the deepest part of you.

Now – how would you feel, if everywhere you turned, you saw one of those degenerates being honored?

What if you saw their names on memorials? Road signs? Local business signs? Or on maps, festival posters, Facebook Group names?

As you go about your life, you and your spouse, your kids, your aunts and uncles, your parents, your grandparents, your cousins, your friends, your colleagues, everyone in your immediate circle, must constantly confront those signs.

Driving through town, buying a cup of coffee, pumping gas, or going to the local hardware store: you are constantly being reminded by businesses proudly displaying the name of a murderer.

Would we be comfortable with a town named after a domestic terrorist, such as Ted Kacyznksi (The Unabomber)? Timothy McVeigh (Oklahoma City Bombing)? Nikolas Cruz (Parkland High School shooter)?

You see where I’m going with this.

But hundreds of people who live in the town of Kelseyville do not.

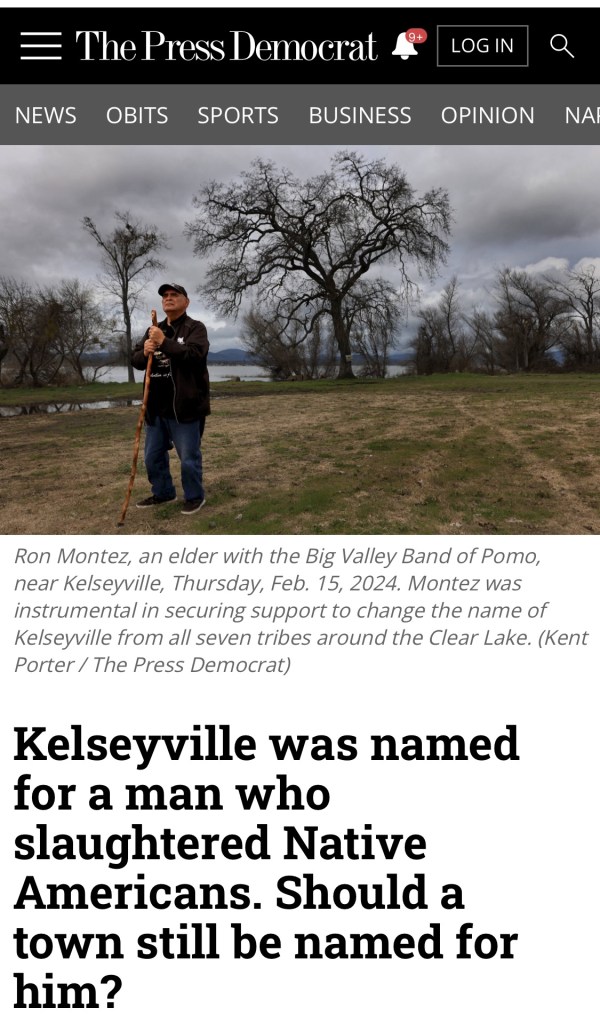

This town, which I never speak of by its current name (I use the term “K-ville” instead), lies a few miles to the east of my home on the Big Valley Band of Pomo Indians Rancheria, where I live with my husband, Ron (he’s quoted and pictured in the article below, which also quotes me in relation to that essay I wrote years ago).

To me, and to every Native person I know, renaming this town to Konocti – the traditional name of the local mountain, and one that all seven federally recognized Tribes in Lake County have agreed to – is a no-brainer.

But to hundreds of K-ville residents who oppose the renaming, their fight has become the new face of racism.

“Leave the past in the past,” is a common refrain: it is one that has swept through communities in the United States opposed to the teaching of any parts of this nation’s history of genocide, land invasion, slavery, red-lining, discrimination, etc. that make us uncomfortable.

“It’s racism,” says my husband, along with every other Pomo we know within a hundred-mile radius of K-ville.

Witnessing how one set of humans can so easily negate the humanity of another set of humans – repeatedly and viciously – makes me sick, in every way that a human can feel sick.

My shoulders tense, my stomach roils.

And I cannot comprehend it.

I was raised in the Mennonite faith, and I have worshipped alongside Pentecostals, Baptists, Methodists, Episcopalians, Unitarian Universalists, Presbyterians, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, and Hindus.

Never, ever, in any faith tradition that I have witnessed, has anyone of compassion and integrity called for the erasure of another people’s traumatic reality.

Yet this is where we are, in the year 2024, in a remote county within one of the most progressive regions in the Divided States of America.

We are sick.

Wow, what an article. So much I, and presumably many of my peers never knew about our local history. Thought provoking, and I hope your exposure of these hard truths will reach as wide an audience as possible.